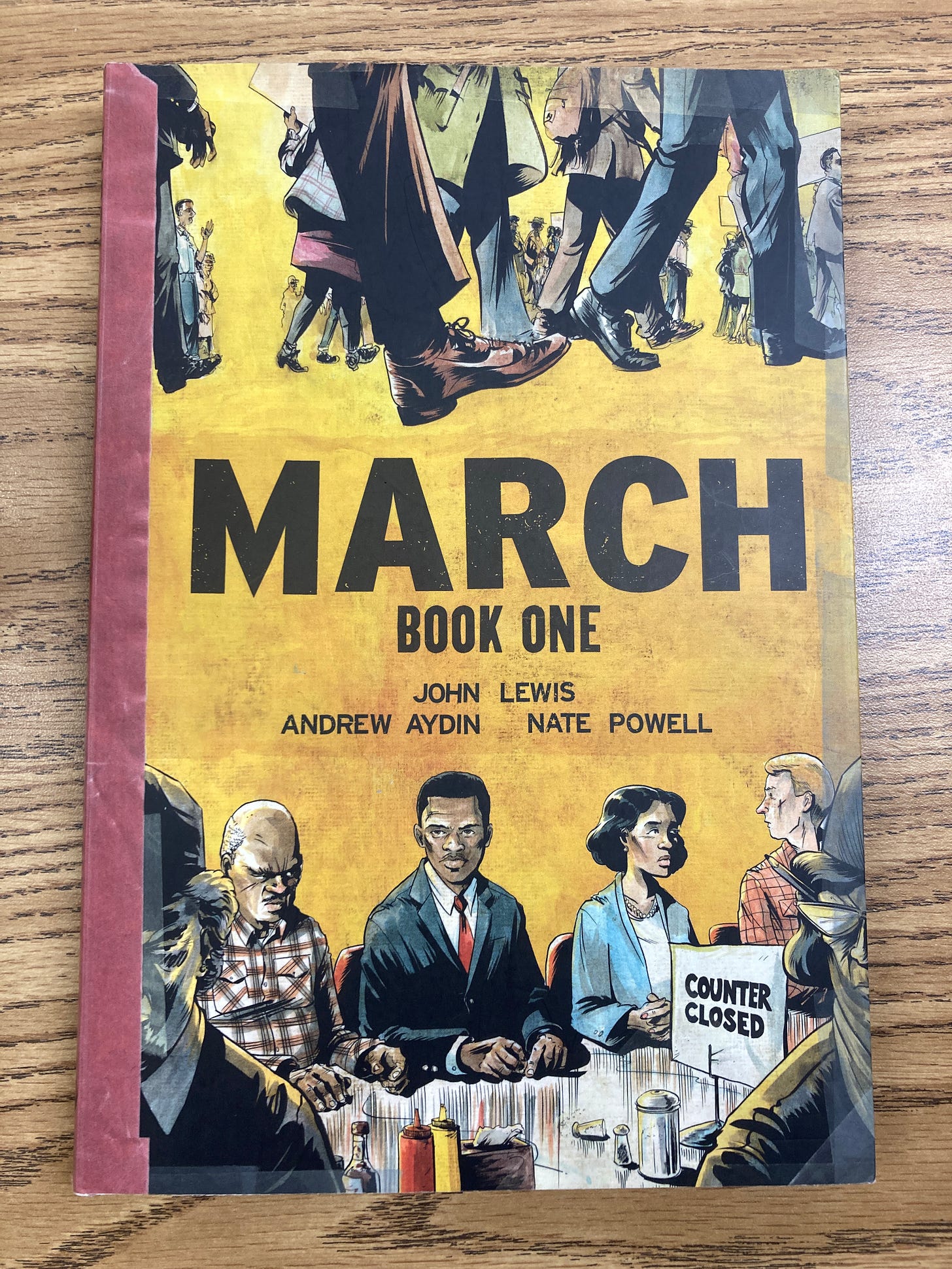

March by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, Nate Powell

2013 Top Shelf Productions

The other day at school, the teacher asked me to pull a group of kids who had already passed the WorkKeys test, an exam that tests their ability to read and write relative to their future work lives, while she remediated the handful who had not.

Four of us walked out of the classroom with our copies of John Lewis’s graphic novel March: Book One in hand.

Prior to coming to teaching late in my working life, I had never even heard of a graphic novel; I am not sure they existed when I was coming up, and even if they did, not being a consumer of comic books, I likely never would have gravitated to the format. Yet my opinion of graphic novels started to change when I taught fifth grade and encountered reluctant readers a number of years ago. Graphic novels were the only thing that motivated those kids to put a book between their fingers. When the classroom library acquired a new graphic novel series, even the most recalcitrant of students was angling for a copy, as was a newly arrived Bangladeshi pupil with limited English.

Suddenly, I was all in as far as graphic novels were concerned.

These days, as an instructional assistant working with special education students in a high school with a largely black and brown student body most of whom live less than privileged lives, I understand the role a graphic novel can play in a student’s education, the possibility it affords. My students are bright teenagers who have, at best, a tenuous relationship with learning. My students, like all teenagers, don’t know anything about the world outside their own lives, and the allure of their phones together with the hand that life has dealt them make it unlikely that they will ever have a relationship with literature.

The other day proved different though. The four of us walked the short distance to the English department’s workroom, where we sat down at an enormous oval table that dominated the room like an oversized surfboard. Our English department classrooms, unlike the seminar rooms of my freshman literature class at Mount Holyoke, do not have workshop tables that foster discussion, yet unwittingly, our group had found a place that did.

Despite several attempts on the students’ part to veer off topic, we opened March to page 28, where the author, future Congressman, Civil Rights, and social justice icon John Lewis, is describing his early life in rural Alabama where as a boy he fostered a fondness for the family’s chickens, even building a homemade incubator for those who did not flourish. In addition to his preternatural attachment to the chickens, Lewis had a budding interest in becoming a preacher. Each night he quoted Scripture to the birds.

As more and more tardy students arrived at the teacher workroom to join our newly minted seminar, each of the teenagers, no matter their reading fluency, read a page of the book. We stopped and talked about Congressman Lewis. We talked about Christianity, baptism, religion in general, Islam and Buddhism. When Lewis described how an uncle took him on a road trip up north in 1951, we talked about the Green Book and Jim Crowe laws. Later the conversation steered toward the topic of mentors, and one senior, who once told me that in middle school he “ran the school,” but who has since evolved into a young man serious about his future as an auto-mechanic and businessman, pulled out his wallet and rifled through a stack of business cards bequeathed to him by various mentors and would-be mentors.

All of the students, save one, said they have at least one mentor, and this filled me with hope for their futures. I suspect Congressman John Lewis (D-GA) was smiling down from heaven on his legacy.

Sheila, sounds like quite a day! How wonderful to have those kids make such a connection!

Mentoring assures young people that there is someone who cares about them, that they are not alone in dealing with challenges, and makes them feel like they matter. Sheila - it seems like you’ve become a group mentor. Those kids are so lucky to have you.